|

This page includes information ("Good Practice")

on the treatment of iron, as well as a section ("Understanding

Ironwork") to help you understand iron fence terminology. We also

provide information on a few of the more common fence manufacturers who sold to

cemeteries in the Southeast ("Brief

Synopsis of a few Cemetery Fence Companies").

Good Practice

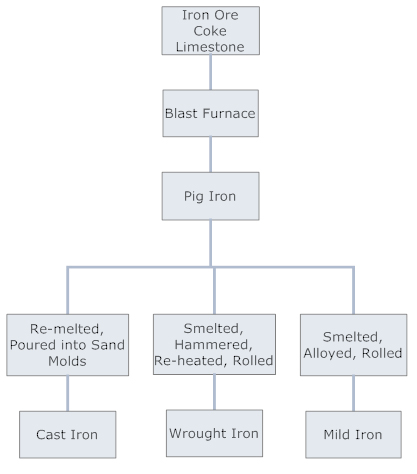

Understanding Iron

The two most common metals in

American cemeteries are wrought iron and cast iron. Understanding the

differences will help you better care for these materials.

Wrought iron

(sometimes called puddled or charcoal iron) is the traditional material of the

blacksmith. It is a mixture of nearly pure iron (less than 1% carbon) with up to

5% (but averaging about 2.5%) siliceous (glassy) slags that take the form of

linear fibers. It resists corrosion, is not brittle, and seldom breaks. It soft,

relatively malleable and easily worked. As a result it is often found as

delicate artwork.

Cast iron has a high

carbon content (usually around 3%) that is easily poured into molds -- resulting

in its use to replicate fence details. It is hard and brittle, and hence

unsuitable for shaping by hammering, rolling, or pressing. When fractured, cast

iron often has a gray, grainy appearance.

There are other metals found

in American cemeteries, such as mild steel (cheaper than wrought, but exhibiting

far less resistance to corrosion and unsuitable for repair work) and zinc

(sometimes mistakenly called white bronze).

Retention of Original Elements

Every effort should be made to retain all existing ironwork at

historic cemeteries, regardless of condition. Replacement with new materials is

not only aesthetically inappropriate, but often causes galvanic reactions

between dissimilar metals. When existing ironwork is incomplete, a reasonable

preservation solution to repair and maintain the remaining work rather than

add historically inappropriate and incorrect substitutes. If replacement is

desired, salvage of matching elements is preferred over recasting. Replication

is typically not an appropriate choice since it is by far the most expensive

course of action, and is often done very poorly.

Securing

Elements

Owners of cemetery ironwork should be aware that there is a

growing illicit market for cemetery gates, fence sections, benches, and

ironwork. It is critical that you take steps to ensure that all materials are

appropriately secured against theft. There is an article that will help you

secure your gates

available from the National Park Service (and written by Chicora's director, Dr.

Michael Trinkley). The techniques in that article can also be adapted to secure

fence sections and other ironwork. A critical component of your maintenance plan

should be to inventory and photograph your resources -- so you know what you

have and, if necessary, can later identify elements as belonging to your

cemetery. Owners of cemetery ironwork should be aware that there is a

growing illicit market for cemetery gates, fence sections, benches, and

ironwork. It is critical that you take steps to ensure that all materials are

appropriately secured against theft. There is an article that will help you

secure your gates

available from the National Park Service (and written by Chicora's director, Dr.

Michael Trinkley). The techniques in that article can also be adapted to secure

fence sections and other ironwork. A critical component of your maintenance plan

should be to inventory and photograph your resources -- so you know what you

have and, if necessary, can later identify elements as belonging to your

cemetery.

What you never want to do is simply leave items leaning up

against a tree in the cemetery. If the ironwork looks abandoned it is an easy

target for thieves.

Painting

The single best protection of ironwork is maintenance -- and

this revolves around painting. In fact, many suggest that ironwork should be

repainted every five to 10 years, or at the first signs of rust. Rust happens

anywhere that you have iron, water (or moisture), and oxygen. Eliminate one of

the three and you've solved the problem -- but of course this is impossible;

while we can't prevent rust, we should strive to retard its return.

The first step is to evaluate the corrosion problem --

determine what is causing the corrosion. Once you figure out the problem, you

may be able to attack at least part of the problem through repair and

preventative maintenance.

Joints are especially vulnerable locations in ironwork --

water will be drawn into these spaces by capillary action and corrosion can be

very severe. Another problem area is where cast and wrought iron come into

contact since this creates corrosion from electrolytic action. Often you'll see

the cast iron top rail laid on a wrought iron connector being pushed up and

split by corrosion. Simply sealing this joint doesn't eliminate the problem --

it only seals in the moisture and corrosion continues unabated. It necessary to

stabilize (and often remove) the corrosion -- only then can the joint be sealed

(red lead putty was originally used, but today a

polyurethane-based, non-sag elastomeric sealant is

usually more practical).

Another problem occurs when ironwork is anchored in damp

stonework. As the iron rusts it expands to many times its original size,

exerting pressure on the stone and ultimately shattering the stone. Often the

ironwork was mounted into the stone using molten lead -- this combination, too,

can cause serious corrosion. Another, even greater, problem is found when iron

was mounted using molted sulfur -- this causes very rapid corrosion.

Consequently, sometimes the first step in painting is making necessary repairs

to help minimize future problems -- and a conservator can advise you on these

issues.

When problem areas are addressed, its time to think about

painting. But first you must deal with the existing corrosion. Just as in other

painting jobs the hard work comes in preparation -- not painting. There are

essentially two options -- remove the corrosion or convert the corrosion into

something stable.

Removing corrosion can be a daunting task, especially on

something as detailed and intricate as an iron fence or gate. Hand preparation

using a wire brush is good at removing bulk corrosion, but it is hard work and

leaves much corrosion untouched. An alternative that many select because of its

ease is abrasive cleaning. In general, conservators do not recommend this

approach. While cast iron is pretty hard, wrought iron is softer and the surface

can be easily roughened. Using abrasives also removes the mill scale, which is

iron's natural protective coating. If for some reason abrasive cleaning is

essential its advisable to use a soft abrasive, such as ground shell, at a low

psi. Final working pressure is not likely to exceed 60-70 psi with a working

distance of at least 12 inches.

Once cleaned of corrosion it is critical that a rust inhibitor

be applied quickly. There are a variety of suitable primers -- what is more

important than the choice is that two primer coats be applied. With one primer

coat it is almost impossible to produce a continuous film without pinholes. A

second coat is essential -- and works better than a second topcoat since it is

designed to inhibit rust from breaking through the final paint coat. Once cleaned of corrosion it is critical that a rust inhibitor

be applied quickly. There are a variety of suitable primers -- what is more

important than the choice is that two primer coats be applied. With one primer

coat it is almost impossible to produce a continuous film without pinholes. A

second coat is essential -- and works better than a second topcoat since it is

designed to inhibit rust from breaking through the final paint coat.

Your

paint should be an alkyd rather than latex and should be designed for use with

the primer you have selected. Some suggest the use of new generation epoxy

paints, which are very durable. They are very difficult, however, to remove and

should not be your first choice. In no case should the paint be applied thickly

-- this obscures detail and does not appreciably lengthen the lifespan of the

paint. In fact, thick paint can chip more easily than a thinner coat. An

appropriate color, lacking any other historic evidence, is flat black. Gloss

enamels should be avoided.

Another option is the use of a rust converter. These

paint-like products are applied directly to rusty metal after only minimal

surface preparation -- using light scraping and degreasing. Converters stabilize

the corrosion, converting the rust into a more stable chemical. A common

formulation is tannic acid, that reacts with rust to form a bluish-black ferric

tannate, combined with a polymer to consolidate the rust. The benefits of a rust

converter go beyond ease of use -- it is virtually impossible (even with

abrasives) to get into every crack and crevice of ironwork -- but a liquid

converter helps ensure that there are no hidden rust pockets. The

Canadian Conservation Center

tested a

range of products in 1992, finally recommending three. Unfortunately since that

time two have been replaced by untested products. The one product that is

still readily available is the

Rust-Oleam Rust Reformer, which we routinely use. Remember that after

conversion it is still critical to use an appropriate topcoat, following the

same instructions as offered above. there are no hidden rust pockets. The

Canadian Conservation Center

tested a

range of products in 1992, finally recommending three. Unfortunately since that

time two have been replaced by untested products. The one product that is

still readily available is the

Rust-Oleam Rust Reformer, which we routinely use. Remember that after

conversion it is still critical to use an appropriate topcoat, following the

same instructions as offered above.

Repairs

Repair may include reattachment of elements. Ideally repairs

should be made in a manner consistent with original construction. For example,

newel posts were often originally attached to the stone or masonry base using a

threaded rod packed in lead. When this assembly is loose, the ideal approach is

to replace the threaded rod using a 306 or 316 stainless steel rod and repacking

it using lead standing proud or an epoxy filler.

It may also be appropriate to use small stainless steel braces

with stainless steel nuts and bolts to reattach coping rails to posts. While

welding is often expedient (and may be better than inappropriate mending), this

approach causes a radical change to the fence. Once welded pieces are no longer

able to move with expansion/contraction cycles, there is a build-up of internal

stresses that may lead to yet additional structural problems.

In addition, while wrought iron is easy to weld because of its

low carbon content, cast iron, with its higher carbon content, is difficult to

weld. The reason that cast iron is so hard to weld without cracking is its

rigidity. When one small area is heated, causing it to expand, the unheated

areas resist -- and crack. An alternative is to braze cast iron since this

approach requires much less heat. Welding on cast iron should be done only by

firms specializing in this work and capable of preheating the elements.

When used, welds should be continuous (not spot) and ground

smooth. This will help eliminate any gaps or crevices where water can collect

and corrosion can take place. When finished, it should be difficult to

distinguish the weld -- the original metal should blend or flow directly into

the reattached part. Welds in wrought iron must also be the full depth of

the material and not just on the surface.

Fence Before Repair and Treatment

Fence After Repair and Painting

Understanding Ironwork

Fence

Styles

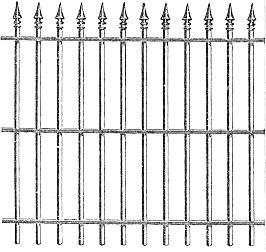

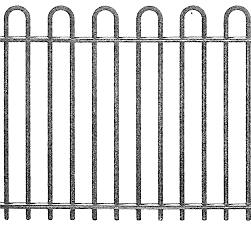

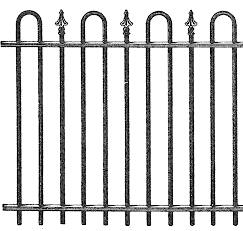

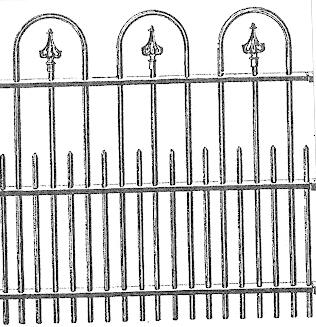

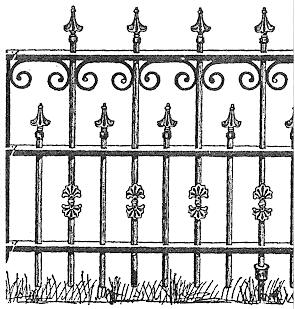

There are essentially three "styles" or types of fences

(although there are many sub-types or varieties).

Perhaps the most common (at least today) are the wrought or

cast fences. These were manufactured by companies such as Stewart Iron Works

and consisted of either two or three wrought rails into (or onto) which were

attached various cast elements. These are often classified as picket (either

beveled or with special picket heads), hairpin, hairpin and picket, bow and

picket, and bow and hairpin, although a great variety of other designs

(short-long pickets, scroll, etc.) can be found. Posts were often of three

distinct types: line posts, panel, square/solid (usually cast), and open or scroll.

Picket Picket

Hairpin Hairpin

Hairpin

and picket Hairpin

and picket

Bow and

picket Bow and

picket

Bow and hairpin

Bow and hairpin

Scalloped

picket Scalloped

picket

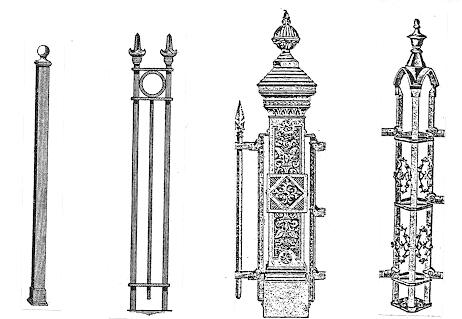

Post forms: line posts (solid, often wrought), panel posts,

square/solid (usually cast), and open or scroll.

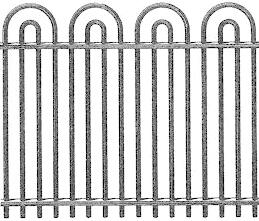

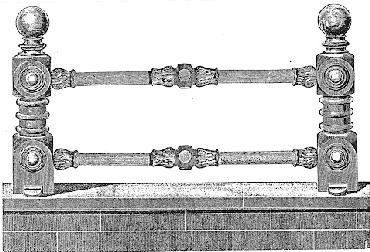

Found at many cemeteries are pipe fences,

also called "gas pipe fences" in many catalogs. There is much less information

about these designs, although many can be quite attractive. They often were

galvanized, frequently with white metal decorative elements. They may be found

set in stone posts using lead or in metal posts with a white Found at many cemeteries are pipe fences,

also called "gas pipe fences" in many catalogs. There is much less information

about these designs, although many can be quite attractive. They often were

galvanized, frequently with white metal decorative elements. They may be found

set in stone posts using lead or in metal posts with a white metal clip. They

may also be found as low fences set on stone walls (as in this line drawing).

metal clip. They

may also be found as low fences set on stone walls (as in this line drawing).

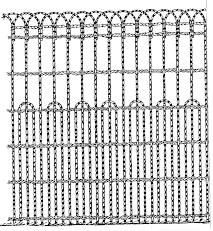

A third fence type is woven wire. These were the least

expensive and many were very intricate. Unfortunately they are also the least

well preserved, often being damaged by mowing and quickly corroding. A few may

still be found around family plots or individual graves (where they were often

only a hot high), as arbors and other decorative devices.

Sources of Replacement Fences

and Parts

There are likely many places that woven wire fencing can still be

found, but here are two sources we have identified on-line:

Hutchinson, Inc. (H-W Brand), 1228 Zimmerman Drive, Grinnell, IA 50112,

(800) 588-6155

American

Fence & Supply Co., 6612 Harborside Dr., Galveston, TX 77554, (409) 744-7131

Repair parts for decorative cast and wrought fences:

Lee Custom Iron, 508

East Frank St., Kalamazoo, Michigan 49007, (269) 290-4009

Texas Iron Fence

& Gate Co., PO Box 839, Decatur, TX 76234, (940) 627-2718

King Architectural

Metals, 6340 Valley View St., Los Angeles, CA 90620, (800) 542-2379

Wiemann Metalcraft,

639

West 41st St, Tulsa, OK 74107, (918)

592-1700

Heritage Cast Iron USA, 639 W 41st St., Tulsa,

OK 74107, (918) 592-1700

Repair parts for pipe rail fences:

Architectural Iron Co., P.O. Box 126, Milford, PA 18337, (800) 442-4766

One of the few original manufacturers,

Stewart Iron Works, is

still in business. While under new management, their past service has been

variable and often poor.

Brief

Synopsis of A Few Cemetery Fence Companies

Fence companies can often be identified by the shields they

placed on their gates. The example to the left is a shield for the American

Fence and Iron Works Co., Cincinnati, Ohio -- a company for which we have no

information at the present time. In some cases they can be identified by

distinct styles. And in other cases, some fence component is marked with a

catalog number that can be traced to a specific company In the example below

there is the number "114" at the base of the left gate post. Recording as much

detail as possible about the fence can sometimes

help

you determine when the fencing was added and can even help you better understand

trade patterns for the local community. help

you determine when the fencing was added and can even help you better understand

trade patterns for the local community.

Champion Iron Fence Company -- Incorporated as Champion

Fence Company in 1876 by William L. Walker, James Young, William H. Young, B.G.

Devoe, and Henry Price with a factory on Franklin Street in Kenton, Ohio. The

works moved briefly to Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania in 1877, returning to Kenton in

1878. In 1878 it was incorporated as Champion Iron Fence Company. Date of

dissolution not know, but is post 1884 (History of Hardin County, Ohio).

In fact, the company provided the fence for the Iolani Palace

in Honolulu as late as 1892 (Hawaiian

Gazette March 1, 1892 page 11:1). Chicora Resources: copies of 1884 Illustrated Supplement Catalog; ca. 188_

Miniature Catalog No. 12. Pennsylvania in 1877, returning to Kenton in

1878. In 1878 it was incorporated as Champion Iron Fence Company. Date of

dissolution not know, but is post 1884 (History of Hardin County, Ohio).

In fact, the company provided the fence for the Iolani Palace

in Honolulu as late as 1892 (Hawaiian

Gazette March 1, 1892 page 11:1). Chicora Resources: copies of 1884 Illustrated Supplement Catalog; ca. 188_

Miniature Catalog No. 12.

Cleaveland Fence Co. -- This company, out of

Indianapolis, Indiana, was in business from at least 1893 through 1901 based on the information found thus far. In

was located for at least part of that time at 19 Biddle Street and employed

about 30 men. We haven't found any catalogs, but have identified this company's

fence at Magnolia Cemetery in Thomasville, Georgia. This example is of an ornate

wire fence with the company's name on its posts.

C. Hanika & Sons -- It appears that the company may

have begun in Celina, Ohio in the late nineteenth century. It continued to

operate through the early twentieth century, but was no longer in Celina by

1907. An ad from that date, however, places the firm, still doing business as C. Hanika & Sons Co., in Muncie, Indiana. It perhaps merged with other Hanika

family associated with the Muncie Architectural Iron Works, but appears under

the name Ca. Hanika & Sons by 1907. The firm either no longer existed by 1911 or

had merged with the Muncie Ornamental Iron Works (Celina Ohio Business

Directory; Mercer County, Ohio History; Emerson's Muncie Directory).

Chicora resources include only a 1907 advertisement for the firm in Muncie,

Indiana.

Cincinnati Iron Fence Company -- No corporate history

is available, but appears to have produced fences from the late nineteenth through

early twentieth centuries. Chicora resources include photocopied portions of

three catalogs, Catalogue No. 10, Price List from Catalogue No.

75 85, and Catalogue 19r.

Crockett Iron Works – Located in Macon, Georgia this

firm began in 1869. It remained a relatively small operation ,

using only 30 men in 1887. By the 1890s the firm had gone out of business. In

addition to fences, the firm also produced steam engines and cane crushers. ,

using only 30 men in 1887. By the 1890s the firm had gone out of business. In

addition to fences, the firm also produced steam engines and cane crushers.

Hinderer’s Iron Works

-- This firm was located on Camp Street in New

Orleans. Producing cast iron fences, benches, fountains, lampposts, and urns,

they are reported to have begun in 1884 and continued into the late 1920s.

Republic Fence & Gate Company -- No

corporate history is currently available, but this company was a major producer

of woven wire fences from its North Chicago, Illinois factory. While such

"ornamental" wire fences were less expensive, they also are often heavily

damaged, both by corrosion and also by lawn mowers. Fences for cemetery lots

were provided (with the company remarking in one catalog, "on account of the

advertising derived, we make special prices to Cemeteries, Churches and Public

Institutions") as well as trellis-fabric and "lawn border fabric" that is

sometimes found enclosing single graves, especially in African American

cemeteries. Chicora resources include one catalog, Republic Ornamental Fence

and Gates, Catalog No. 3 (n.d.).

Rogers Fence Company -- Incorporated in 1882 and first

appears in the Williams City Directory (Springfield, Ohio) in 1883. It continues

to be listed under that name through 1891. The name changed to Rogers

Iron Company in 1892 and was then succeeded by the William Bayley Company by

1905. This company continued in business (manufacturing steel and aluminum

windows and steel doors) through ca. 2000 (History of Manufactories of

Springfield, Ohio). Chicora resources: single advertisement in History of

Manufactories of Springfield, Ohio, showing a "bolted, clip and punched

wrought iron rail fence" of two different designs.

Sears Roebuck and Co. -- While the corporate history of

Sears is well know, we don't know when it entered the fencing business. It

appears, however, that Sears acquired its fences from other manufacturers and

installed a Sears label on the product (we are told, for example, that Stewart

Iron Works had a contract with Sears). Consequently, their fencing styles

appear to mirror other manufacturers, such as the Stewart Iron Works. Chicora

resources: 1921 Sears Roebuck and Co. Lawn and Cemetery Steel Picket and Wire

Fabric Fencing catalog.

Springfield Architectural Iron Works -- Located in

Springfield, Ohio, this

firm

was organized in 1889 by Aaron J. Moyer. Mr. Moyer had earlier been the

Superintendent and Secretary of the Roger's Fence Company. How long the company

was in business is unknown. Sources: Portrait and Biographical Album of

Greene and Clark Counties, Ohio, 1890, Chapman Brothers. firm

was organized in 1889 by Aaron J. Moyer. Mr. Moyer had earlier been the

Superintendent and Secretary of the Roger's Fence Company. How long the company

was in business is unknown. Sources: Portrait and Biographical Album of

Greene and Clark Counties, Ohio, 1890, Chapman Brothers.

Stewart Iron Works Company -- This is one of the

largest manufacturers of iron fencing found in cemeteries. It began in 1886 in

Covington, Kentucky. By 1903 a portion of the company's work was housed in

Cincinnati, although this operation closed in 1914. Steward Iron Works is still

in operation today, using it original patterns and performing repair on old iron

fencing as well as manufacturing new fencing ("Stewart Iron Works, A Kentucky

Centenary Company" in Northern Kentucky Heritage). Chicora resources

include ca. 1910 Catalog No. 60-A; 1928 Cemetery Fences and Entrance Gates

(AIA File 14-K); 1928 Fences and Gates for Every Purpose; modern (ca.

2001) catalogs.

Valley Forge -- Began in 1873 and is reported to have

manufactured wrought steel fences exclusively. In 1901 the proprietor was H.O.

Nelson and the

company was located in Knoxville, Tennessee. It appears to have

ceased operation ca. 1903. (Kephart's Manufacturers of Knoxville, Tennessee;

Knoxville City Directories). Chicora resources: only an add from the 1902

Knoxville City Directory, no catalogs. company was located in Knoxville, Tennessee. It appears to have

ceased operation ca. 1903. (Kephart's Manufacturers of Knoxville, Tennessee;

Knoxville City Directories). Chicora resources: only an add from the 1902

Knoxville City Directory, no catalogs.

Valley Iron Works -- Began in 1872 and continued in

operation until 1876. Located in Mercer County, Ohio and was apparently also

known as the Sharon Iron and Brass Foundry (History of Mercer County).

W.A. Snow Iron Works -- located in Chelsea,

Massachusetts, no other corporate history currently available. Chicora resources

include a copy of the 1915 Wrought Iron Fences and Gates catalog. This is

one of the few catalogs we have seen which also illustrates several varieties of

woven wire fabric fences found in cemeteries.

Wood & Perot -- Robert Wood began business as a blacksmith in 1838,

but soon expanded into cast iron work. From 1857 to

1865, the firm was known as Wood & Perot. After 1865, it was again only Robert

Wood & Co. until they filed for bankruptcy, about 1878. Wood & Perot was based

in Philadelphia, but a branch called Wood, Miltenberger & Co. was based in New

Orleans and it appears this New Orleans firm distributed a number of items using

the Wood & Perot stamp (in at least one document it was described as a

“branch”). The firm was responsible for a large number of fence designs, as well

as various furnishings, such as urns and benches. Perhaps of most interest are

the iron family vaults they constructed.

-- Robert Wood began business as a blacksmith in 1838,

but soon expanded into cast iron work. From 1857 to

1865, the firm was known as Wood & Perot. After 1865, it was again only Robert

Wood & Co. until they filed for bankruptcy, about 1878. Wood & Perot was based

in Philadelphia, but a branch called Wood, Miltenberger & Co. was based in New

Orleans and it appears this New Orleans firm distributed a number of items using

the Wood & Perot stamp (in at least one document it was described as a

“branch”). The firm was responsible for a large number of fence designs, as well

as various furnishings, such as urns and benches. Perhaps of most interest are

the iron family vaults they constructed.

W.T. Barbee Fence Works -- This company was apparently

located in Chicago, Illinois (the address varies with time), with another

factory in

Lafayette,

Indiana. They were in business by at least 1901, but ceased production sometime

between 1923 and 1928. Lafayette,

Indiana. They were in business by at least 1901, but ceased production sometime

between 1923 and 1928.

|