|

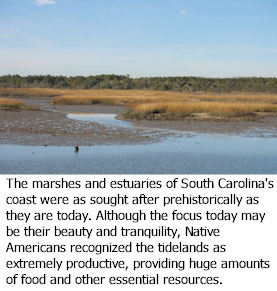

About 4,000

B.P. (around 2,000 B.C.)

the environment began to

change along the South

Carolina coast. Sea levels

rose from a low of about 12

feet below their current

levels to almost modern

levels. This increase in sea

level created the

marshes, inlets, and tidal

areas that today make the

coast such an

environmentally rich and

productive area. This

ecological change also

brought about significant

changes in the way

prehistoric South

Carolinians, or

Native Americans,

interacted with their

environment. About 4,000

B.P. (around 2,000 B.C.)

the environment began to

change along the South

Carolina coast. Sea levels

rose from a low of about 12

feet below their current

levels to almost modern

levels. This increase in sea

level created the

marshes, inlets, and tidal

areas that today make the

coast such an

environmentally rich and

productive area. This

ecological change also

brought about significant

changes in the way

prehistoric South

Carolinians, or

Native Americans,

interacted with their

environment.

The Native American groups

that had been seasonally

moving from location to

location, hunting deer and

collecting nuts, began to

understand that there was a

great diversity and

abundance of foods on the

coast. So many foods to

choose from in one place

provided another option –

nearly permanent

settlements.

These people began to

collect shellfish and trap

fish using nets. They

supplemented their diet by

collecting occasional marsh

visitors, such as marsh

rabbits, turtles, opossums,

snakes, and even alligator.

They still hunted deer and

collected hickory nuts.

However, by adding a variety

of other foods, their diet

improved and they were able

to live in one place

longer. This reduced the

amount of time they had to

move from one location to

another. This is what

archaeologists call “sedentism.”

Shell Rings and Shell

Middens Shell Rings and Shell

Middens

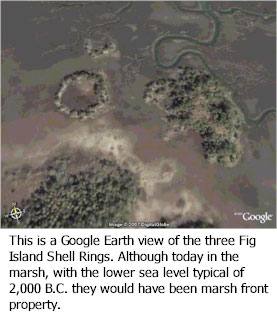

An

unusual type of

archaeological site

developed during this period

–

doughnut-shaped piles of

shell that

archaeologists call “shell

rings.” Although these

rings are found in different

sizes, they average about

160 feet in diameter, 4 to 5

feet in height, and have a

width at their base of about

45 feet. There are

several theories about

the function of these sites,

but what we know is that

they contain a huge

assortment of floral and

faunal remains – showing us

the varied diet of the

people who lived on or

around them.

Because these people existed

so long ago, archaeologists

cannot associate them with

any modern Native American

tribal groups. Instead,

these Native Americans are

known as the “Thom’s Creek”

people. Thom’s Creek is

also the name of the type of

pottery these people made.

Thom’s Creek pottery has a

sandy texture and is often

decorated with various

punctuations. Found along

the South Carolina coast, it

is associated with the shell

rings, and dates from about

2,000 B.C. to 500 B.C. It

is one of the earliest types

of pottery made by the

Native Americans in South

Carolina. While the Thom’s Creek

people are best known for

their shell rings, these

were not the only sites they

left behind.

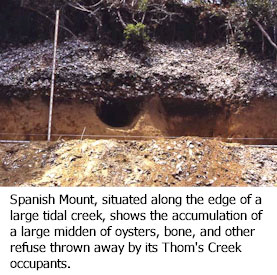

In

addition to shell rings,

there are also huge

shell mounds or middens

such as

Spanish Mount on Edisto

Island (Charleston County)

which several USC

archaeological field schools

have studied. Probably the

most common Thom’s Creek

sites are actually small

accumulations of shells and

refuse (the garbage thrown

away by the Thom’s Creek

people), and they have

received very little study.

Recently, however, with the

cooperation of Carolina Park

Associates, archaeologists

have been given a unique

opportunity to examine one

such site. In

addition to shell rings,

there are also huge

shell mounds or middens

such as

Spanish Mount on Edisto

Island (Charleston County)

which several USC

archaeological field schools

have studied. Probably the

most common Thom’s Creek

sites are actually small

accumulations of shells and

refuse (the garbage thrown

away by the Thom’s Creek

people), and they have

received very little study.

Recently, however, with the

cooperation of Carolina Park

Associates, archaeologists

have been given a unique

opportunity to examine one

such site.

Carolina Park Associates

and 38CH1693

Known as

38CH1693, this site was

discovered in 2003, at the

corner of Airport Road and

US 17,

during routine

archaeological surveys.

The site was slated for

additional investigation

prior to development. Over

several weeks during the

summer of 2006,

archaeologists with the

Columbia, South Carolina

based Chicora Foundation,

conducted

excavations, made maps, took

samples, and collected

artifacts from this

site.

|

The initial step

in the

archaeological

excavation was

the creation of

an accurate grid

to ensure that

all excavation

units - and the

artifacts they

exposed - could

be precisely

plotted.

Although the

excavation used

shovels, each

level was

precisely noted

and all soil was

either screened

through ¼ mesh

or was

waterscreened

through 1/8-inch

screen. The

water screening

allowed for

recovery of very

small fish bones

and even fish

scales. After

the excavation

all units were

carefully

cleaned, then

photographed and

mapped. |

Research indicates that the

site was situated on a relic

Pleistocene dune ridge.

Located nearby were not only

upland resources, such as

deer and hickory nuts (a

favorite – and nutritious --

food source for Native

Americans), but also springs

and marshes. The springs

supplied fresh drinking

water, while the saltwater

marshes provided fish and

shellfish to eat. Within

just an hour’s walk from

38CH1693, the Thom’s Creek

people could find a variety

of foods – making this an

ideal area to live.

Archaeologists found that

the site was not a shell

midden; instead, it

consisted of several areas

where the inhabitants had

dug pits in which to steam

oysters and other shellfish.

Thus, while there were no

layers of shell, there were

individual pits (what

archaeologists call

“features”). These

features were especially

important because they

helped preserve the food

remains. Recovered from

these features were the

shells of hickory nuts eaten

and discarded into the fire,

as well as animal bones, and

fragments of shellfish. The

features even preserved

pollen and

phytoliths – all of

which were studied by the

Chicora team.

What Was Learned? What Was Learned?

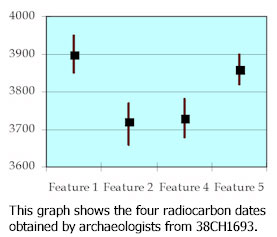

One of the most important

findings was the age of the

site. Using

radiocarbon dating of

the hickory nutshells,

Chicora determined that

38CH1693 dates from

about 1,700 B.C. to 2,000

B.C. In fact, two of the

four dates place occupation

at almost precisely the same

time – 2,135 B.C.

This is important since it

reveals that the site,

occupied during the middle

of the Thom’s Creek period,

was used only briefly.

38CH1693 is giving us a

brief snapshot of life at a

Thom’s Creek site.

Other information, however,

is not so simple to

interpret. For example, the

animal bones suggest the

site was occupied

seasonally, perhaps during

the spring through late

summer or fall. This is

suggested by some of the

fish species present. Not a

lot of deer bone was found,

suggesting that the site was

not used during the fall

when deer rut and are more

common in the coastal area.

On

the other hand, the

ethnobotanical remains

are suggesting of a fall or

early winter occupation.

Grape seeds and hickory

nutshell were two of the

plant foods recovered. Grape

pollen was also found in the

pollen record at the site.

Weedy seeds like greenbrier,

knotweed, and bedstraw were

also present in the

features.

Another common food trash at

the site was shell: oyster,

clam, periwinkle, and stout

tagulus. Although these

occur in different marsh

areas, all are species

common to the area. These

shellfish can be gathered at

any time of year, so they

are not especially good

seasonal indicators.

However, a small parasite of

the oyster, known as

Boonea impressa, is

a good seasonal indicator.

At 38CH1693 these almost

microscopic snails indicate

collection during summer and

fall, as well as early

winter.

The shellfish do tell us

about

procurement strategies

and the importance of

shellfish to the prehistoric

diet. Although periwinkle

are small, they are easily

to collect and might be a

food gathered by older

people or small children.

Moreover, shellfish provide

good quality proteins and

would have been invaluable

in the prehistoric diet.

Since remains from different

seasons are found in the

same refuse – the garbage

thrown away by the Thom’s

Creek people – 38CH1693 may

provide evidence for people

living at the site off and

on during the entire year.

And speaking of garbage,

archaeologists found plenty

of evidence of other things

discarded by these early

occupants of Carolina Park.

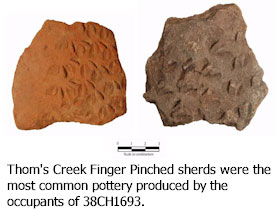

The most common item is

broken pottery. The Thom’s

Creek pottery at this site

was primarily undecorated.

The most common surface

treatment, however, was

finger pinched. Made

by pinching the wet clay

between the thumb and

forefinger, the artisan

typically produced linear

arrangements of this design

around the vessel. Other

decorations included finger

smoothed, and punctuated. The

pots were about 13-14 inches

in diameter, although a few

were as small as 6-inches.

Even when these pots were

broken, they were not

necessarily discarded. Some

were actually repaired and

reused. By drilling holes on

each side of the crack, and

lacing the pot together with

sinew, the pieces of the pot

were held together. To make

the pot watertight, or leak

proof, pitch might be

smeared over the break.

Examples of these mending

holes are found in the

38CH1693 collection. And speaking of garbage,

archaeologists found plenty

of evidence of other things

discarded by these early

occupants of Carolina Park.

The most common item is

broken pottery. The Thom’s

Creek pottery at this site

was primarily undecorated.

The most common surface

treatment, however, was

finger pinched. Made

by pinching the wet clay

between the thumb and

forefinger, the artisan

typically produced linear

arrangements of this design

around the vessel. Other

decorations included finger

smoothed, and punctuated. The

pots were about 13-14 inches

in diameter, although a few

were as small as 6-inches.

Even when these pots were

broken, they were not

necessarily discarded. Some

were actually repaired and

reused. By drilling holes on

each side of the crack, and

lacing the pot together with

sinew, the pieces of the pot

were held together. To make

the pot watertight, or leak

proof, pitch might be

smeared over the break.

Examples of these mending

holes are found in the

38CH1693 collection.

When sherds (bits of broken

pottery) were thrown away

they might still be picked

up and used, or recycled, –

most commonly as

abraders or hones.

The Thom’s Creek people used

them to shape and smooth

bone tools. These bones are

thought to have been used to

weave the nets for

collecting small fish. Other

bones were sharpened to make

tips

for spears (the

bow and arrow was not

invented for another 2,000

or so years).

Although a few stone flakes

were found at 38CH1693, no

finished tools were

recovered by archaeologists.

This is probably because the

coast has few sources of

stone, making it a highly

prized and carefully tended

object. Stone points might

be resharpened, but they

wouldn’t often be lost.

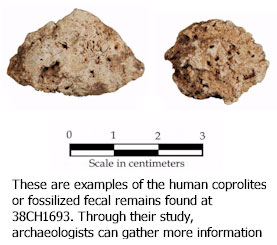

Another interesting find is

what archaeologists call a

coprolites – a fancy

word for

fossilized fecal material.

In a shell-rich environment

the organic matter can be

replaced by calcium, helping

to preserve these remains.

Identified as human based on

size, shape, and contents,

they can be used to better

study exactly what Thom’s

Creek people were eating. Another interesting find is

what archaeologists call a

coprolites – a fancy

word for

fossilized fecal material.

In a shell-rich environment

the organic matter can be

replaced by calcium, helping

to preserve these remains.

Identified as human based on

size, shape, and contents,

they can be used to better

study exactly what Thom’s

Creek people were eating.

Unlike the condensed for

television accounts of

archaeology, the research at

38CH1693 reflects the

reality of archaeology.

After several weeks of

careful but exhausting

excavation, followed by

months of equally

painstaking analysis, we

know a little more about how

the Thom’s Creek people

lived. There is no major

breakthrough or amazing

discovery – just hard work

that gradually builds on

itself to allow us, bit by

bit, to better understand

our ancestry and the history

of South Carolina.

For More Information

-

Read the entire Chicora

report on excavations at

38CH1693

-

Another pdf download is

the 2002 National Park

Service test excavations

at the Fig Island Shell

Ring,

available here.

-

A brief overview of

South Carolina

archaeology is available

here [link to Chicora’s

SC Archaeology page].

-

If your local public

library doesn’t have

these books, you can ask

that they be obtained

for you through

interlibrary loan, a

free service:

|